Not all the holy mountains in the history of the world are natural, formed by the shifting of tectonic plates or the sudden, catastrophic opening of “the fountains of the great deep.” The Tower of Babel was one such artificial mountain. Babel was humanity’s attempt to force its way back into the divine council.

At Babel, mankind tried to storm the castle of God.

For generations, well-meaning Bible teachers have presented the story of Babel as an object lesson on the dangers of pride. Those foolish people were so arrogant they thought they could build a tower high enough to reach heaven!

With all due respect to those teachers, that’s an insult to the intelligence of our ancestors, if you think about it. And it’s a disservice to people in church who want to know why Yahweh was so offended by this project. Really? God is that insecure?

Look, if big egos were enough to bring God to Earth, He’d never leave.

Babel was not a matter of God taking down some people who’d gotten too big for their britches. The clue to the sin of Babel is in the name.

Remember, the Hebrew prophets loved to play with language. We often find words in the Bible that sound like the original but make a statement—for example, Beelzebub (“lord of the flies”) instead of Beelzebul (“Ba`al the prince”), or Ish-bosheth (“man of a shameful thing”) instead of Ishbaal (“man of Ba`al”). Likewise, the original Akkadian words bāb ilu, which means “gate of god” or “gate of the gods,” is replaced in the Bible with Babel, which is based on the Hebrew word meaning confusion.

Now, there’s a bit of misinformation that must be corrected about the Tower of Babel. Contrary to what you’ve heard, Babel was not in Babylon.

It’s an easy mistake to make. The names sound alike, and Babylon is easily the most famous city of the ancient world. It’s also got a bad reputation, especially to Jews and Christians. Babylon, under the megalomaniacal king Nebuchadnezzar, sacked the Temple in Jerusalem and carried off the hardware for temple service. It makes sense to assume that a building project so offensive that God personally intervened must have been built at Babylon.

But there’s a problem with linking Babylon to the Tower of Babel: Babylon didn’t exist when the tower was built. It didn’t even become a city until about a thousand years after the tower incident, and even then it was an unimportant village for about another 500 years.

Traditions and sources outside the Bible identify the builder of the tower as the shadowy figure named Nimrod. Our best guess is he lived sometime between 3500 and 3100 B.C., a period of history called the Uruk Expansion. This tracks with what little the Bible tells us about Nimrod. In Genesis 10:10, we read “the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, Erech, Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar.”

The land of Shinar is Sumer and Erech is Uruk. Uruk was so important to human history that Nimrod’s homeland is still called Uruk, five thousand years later! We just spell it differently—Iraq.

Accad was the capital city of the Akkadians, which still hasn’t been found, but was somewhere between Babylon and ancient Assyria. Babylon itself was northwest of Uruk, roughly three hundred miles from the Persian Gulf in what is today central Iraq. But it wasn’t founded until around 2300 B.C., at least 700 years after Nimrod, and it wasn’t Babylon as we think about it until the old Babylonian empire emerged in the early part of the 2nd millennium B.C.

So where should we look for the Tower of Babel?

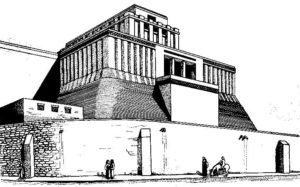

The oldest and largest ziggurat in Mesopotamia was at Eridu, the first city built in Mesopotamia. Scholars put its founding at around 5400 B.C. In recent years, scholars have learned that the name Babylon was interchangeable with other city names, including Eridu. So “Babylon” didn’t always refer to the city of Babylon in ancient texts.

Eridu never dominated the political situation in Sumer after the reigns of its first two kings, Alulim and Alalgar. But as the home city of Enki, god of fresh water, wisdom, and magic, Eridu was so important to Mesopotamian culture that more than three thousand years after Alalgar, Hammurabi the Great was crowned not in Babylon, but in Eridu—even though it had ceased to be a city about three hundred years earlier.

Even as late as the time of Nebuchadnezzar, 1,100 years after Hammurabi, the kings of Babylon still sometimes called themselves LUGAL.NUNki—King of Eridu.

Why? What was the deal with Eridu?

Archaeologists have uncovered eighteen levels of the temple to Enki at Eridu. The oldest levels of the E-abzu, a small structure less than ten feet square, date to the founding of the city. And consider that the spot remained sacred to Enki long after the city was deserted around 2000 B.C. The temple remained in use until the 5th century B.C., nearly five thousand years after the first crude altar was built to accept offerings of fish to Enki, the god of the subterranean aquifer, the abzu.

Now, this is where we tell you that abzu (ab = water + zu = deep) is very likely where we get our English word “abyss.” And the name Enki is a compound word. En is Sumerian for “lord,” and ki is the word for “earth.” Thus, Enki, god of the abzu, was “lord of the earth.”

Do you remember Jesus calling someone “the ruler of this world?” Or Paul referring to “the god of this world?” Who were they talking about?

Yeah. Satan.

#

Here’s another piece to our puzzle: Nimrod was second generation after the flood. His father was Cush, son of Ham, son of Noah.

In Sumerian history, the second king of Uruk after the flood was named Enmerkar, son of Mesh-ki-ang-gasher.

Enmerkar is also a compound word. The prefix en means “lord” and the suffix kar is Sumerian for “hunter.” So Enmerkar was Enmer the Hunter. Sound familiar?

Cush fathered Nimrod; he was the first on earth to be a mighty man.

He was a mighty hunter before the Lord. Therefore it is said, “Like Nimrod a mighty hunter before the Lord.”

Genesis 10:8-9 (ESV), emphasis added

The Hebrews, doing what they loved to do with language, transformed Enmer—the consonants N-M-R (remember, no vowels in ancient Hebrew)—into Nimrod, which makes it sound like marad, the Hebrew word for “rebel.”

Now, get this: An epic poem from about 2000 B.C. called Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta preserves the basic details of the Tower of Babel story, including the confusion of language among the people of Sumer.

We don’t know exactly where Aratta was, but guesses range from northern Iran to Armenia. (Which would be interesting. Not only is Armenia located near the center of an ancient kingdom called Urartu, which may be a cognate for Aratta, it’s where Noah landed his boat—the mountains of Ararat. So it’s possible Nimrod/Enmerkar was trying to intimidate the people—his cousins, basically—who settled near where his great-grandfather landed the ark. But we just don’t know.) Wherever it was, Enmerkar muscled this neighboring kingdom to compel them to send building materials for a couple of projects near and dear to his heart.

Besides building a fabulous temple for Inanna, the goddess of, well, prostitutes, Enmerkar/Nimrod also wanted to expand and upgrade Enki’s abzu—the abyss.

“Let the people of Aratta bring down for me the mountain stones from their mountain, build the great shrine for me, erect the great abode for me, make the great abode, the abode of the gods, famous for me, make my me prosper in Kulaba, make the abzu grow for me like a holy mountain, make Eridug (Eridu) gleam for me like the mountain range, cause the abzu shrine to shine forth for me like the silver in the lode. When in the abzu I utter praise, when I bring the me from Eridug, when, in lordship, I am adorned with the crown like a purified shrine, when I place on my head the holy crown in Unug Kulaba, then may the …… of the great shrine bring me into the jipar, and may the …… of the jipar bring me into the great shrine. May the people marvel admiringly, and may Utu (the sun god) witness it in joy.”1

(Emphasis added)

That’s the issue Yahweh had with it right there. This tower project wasn’t about hubris or pride; it was to build the abode of the gods right on top of the abzu.

Could Nimrod have succeeded? Ask yourself: Why did Yahweh find it necessary to personally put a stop to it? A lot of magnificent pagan temples were built in the ancient world, many of them copying the pyramid-like shape of the ziggurats, from Mesopotamia to Mesoamerica. Why did God stop this one?

We can only speculate, of course, but God had a good reason or we wouldn’t have a record of it in the Bible. Calling Babel a sin of pride is easy, but it drains the story of its spiritual and supernatural context.

In the view of this author, the evidence is compelling. It’s time to correct the history we’ve been taught since Sunday School: Babel was not at Babylon, it was at Eridu. The tower was the temple of the god Enki, Lord of the Earth, the god of the abyss. Its purpose was to create an artificial mount of assembly, the abode of the gods, to which humans had access.

That was something that Yahweh could not allow.

#

The end of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta is mostly missing, but it appears that Enmerkar ultimately triumphed over his rival. Other stories suggest that Enmerkar later marched the army of Uruk to Aratta and conquered it.

This is consistent with archaeological evidence of the Uruk Expansion, which covers the period from about 3500 B.C. to about 3100 B.C. Although scholars usually downplay the violence that created the world’s first empire, Uruk spread its influence as far away as northwest Iran and southeastern Turkey. Pottery from Uruk has been found are more than 500 miles away from the city. To put it into context, Uruk at its peak controlled more territory than Iraq under Saddam Hussein.

This was not always a peaceful endeavor. An ancient city called Hamoukar in northeast Syria was destroyed and burned by an army from Uruk sometime around 3500 B.C. Scholars have identified the origin of the army by the pottery they left behind. Hamoukar was overwhelmed and then burned by attackers who used clay bullets fired from slings to defeat the city’s defenders. Strangely, what appears to have been a trading post from Uruk outside the city was destroyed, too, suggesting that maybe the men sent by Uruk to keep the locals in line had gone native.

That was how the kingdom of Nimrod obtained materials like jewels, copper, silver, lead, gold, timber, wine, and other things that were scarce in the plains of Sumer.

Of course, there is no way we’ll ever know for certain that Nimrod was Enmerkar, and that he was responsible for the Uruk Expansion—which is a nice way of describing the process of conquering everybody within a two-month march of home. Artifacts from Uruk are found everywhere in the Near East, especially a type of pottery called the beveled-rim bowl. This is significant because it offers a glimpse into the way the society of Uruk was organized.

Scholars have found that the society just before the Uruk period, the Ubaid culture, became more stratified as people moved from rural settlements to cities. The Ubaid civilization produced high-quality pottery, identified by black geometric designs on buff or green-colored ceramic. In contrast, around 3500 B.C., the Uruk culture developed the world’s first mass-produced product, the beveled-rim bowl.

The beveled-rim bowl is crude compared to the pottery from the Ubaid culture, but archaeologists have found a lot of them. About three-quarters of all pottery found at Uruk period sites are beveled-rim bowls. Scholars agree that these simple, undecorated bowls were made in molds rather than on wheels, and that they were probably used to measure out barley and oil for workers’ rations.

The way they were produced left the hardened clay too porous to hold liquids like water or beer. (Yes, the Sumerians brewed beer. Enki’s alternate name, Nudimmud, is a compound word: nu = “likeness” + dim = “make” + mud = “beer.” One could argue that Enki is the spirit of our age.) The bowls were cheap and easy to make, so much so that they may have been disposable. At some archaeological sites, large numbers of used, unbroken bowls have been found in big piles. Basically, these cheap bowls were the Sumerian version of Styrofoam fast-food containers.

The concept of measuring out rations implies an employer or controlling central authority responsible for doling out grain and oil to laborers. It’s not a coincidence that the development of these crude bowls happened alongside Uruk’s emergence as an empire. After the flood, which we theorize marked the end of the Ubaid period, people again gravitated to urban settlements where they apparently exchanged their freedom for government rations.

It looks like that’s how Nimrod and his successors, including Gilgamesh, controlled their subjects—moving them off the land and into cities, keeping a tight rein on the means of production and distribution of food and resources.

Now, it’s possible we’re reading more into the evidence than is truly there. It could be that the beveled-rim bowl was nothing more than an easy way for people to carry lunch to work. Will future archaeologists conclude that Americans were paid in carry-out hamburgers because of the billions of Styrofoam containers in our landfills?

Still, given the unprecedented growth of the Uruk empire between about 3500 B.C. and 3100 B.C., it’s not going too far to speculate that the use of mass-produced ration bowls was a symptom of the stratification of society under the rule of Nimrod/Enmerkar and his successors. As in the Ubaid culture, citizens of Uruk found themselves working for hereditary leaders—kings, who justified their rule as ordained by the gods.

As an example, the Sumerian myth Enki and Inanna tells the story of how the divine gifts of civilization, the mes (sounds like “mezz”), were stolen from Enki by the Inanna and transferred from Eridu to Uruk. Enki, always ready for a romp with a goddess, tried to ply Inanna with beer. She maintained her virtue while Enki got drunk, offering her gift after gift as his heart grew merry and his mind grew dim. When he awoke the next day with a hangover, Inanna and the mes were no longer in the abzu. The enraged god sent out his horrible gallu demons (sometimes translated “sea monsters”) to retrieve them, but Inanna escaped and arrived safely back at Uruk, where she dispensed the hundred or so mes to the cheers of a grateful city. Enki realized he’d been duped and accepted a treaty of everlasting peace with Uruk. This tale may be a bit of religious propaganda to justify the transfer of political authority to Uruk.

One more thing: We mentioned earlier that archaeologists at Eridu have found 18 construction layers at the site of Enki’s temple. Some of those layers are below an eight-foot deposit of silt from a massive flood. The most impressive layer of construction, called Temple 1, was huge, a temple on a massive platform with evidence of an even larger foundation that would have risen up to almost the height of the temple itself.

Here’s the thing: Temple 1 was never finished. At the peak of the builders’ architectural achievement, Eridu was suddenly and completely abandoned.

.”.. the Uruk Period … appears to have been brought to a conclusion by no less an event than the total abandonment of the site. … In what appears to have been an almost incredibly short time, drifting sand had filled the deserted buildings of the temple-complex and obliterated all traces of the once prosperous little community.”2

(Emphasis added)

Why? What would possibly cause people who’d committed to building the largest ziggurat in Mesopotamia at the most ancient and important religious site in the known world to just stop work and leave Eridu with the E-abzu unfinished? Could it be…

“Come, let us go down and there confuse their language, so that they may not understand one another’s speech.” So the Lord dispersed them from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city.

Genesis 11:8-9 (ESV), emphasis added

To the Sumerians, and later the Akkadians and Babylonians (who knew him as Ea), Enki was the supernatural actor with the most influence on human history. He was the caretaker of the divine gifts of civilization, the mes (at least until he was tricked by Inanna), and he retained enough prestige for powerful men to justify their reign by claiming kingship over his city, Eridu, for 2,500 years after the city around the temple complex was abandoned.

For one moment in human history, Enki induced a human dupe—Nimrod, the Sumerian king Enmerkar—to build what he hoped would be a new abode of the gods, the bāb ilu, to rival Yahweh’s mount of assembly. It was to be the heart of a one-world totalitarian government.

Yahweh put a stop to it. But as George Santayana wrote, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” The sin of Nimrod is being repeated today by the globalist movement, slowly but surely leading us back to Babylon.

1 Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G. “Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta,” The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.2.3#), retrieved 12/17/16.

2 Safar, Fuʼād; Lloyd, Seton; Muṣṭafá, Muḥammad ʻAlī; Muʼassasah al-ʻĀmmah lil-Āthār wa-al-Turāth. Eridu. Republic of Iraq, Ministry of Culture and Information, State Organization of Antiquites and Heritage, Baghdad, 1981.